Talk with Farhad Fozouni

[This note is originally written in Persian and is translated to English by AI. Original note]

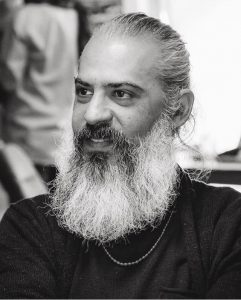

Farhad Fozouni, born in 1978 in Tehran, holds a Bachelor’s degree in Graphic Design from the Islamic Azad University and is a member of the Graphic Designers Association. He has won multiple awards in the fields of graphic design and theater, and has served as a juror for festivals and biennials, including the Silver Sarv and Fajr Theater Poster Festival. He has held the position of artistic director for magazines such as Farhang va Ahang, Honar-e-Farda, Kheradnameh, and Tasvirnameh. He also works as a department head or instructor at art high schools including fine art school, Vizhe school, and Camp Graphic. He has organized several solo exhibitions featuring installation art, sculpture, and painting in Tehran, Germany, Turkey, and elsewhere. He participated as a guest juror in the public call section of the second Patternitecture event, during which we had the opportunity to speak with him.

Question: How do you define a pattern? And what conditions must exist for something to be classified as a pattern?

Answer: I think to answer this question, we need to take a step back and change our perspective. Modern science views the world from the human perspective, but I go a bit further back, like the perspective seen in miniatures, because patterns appear differently from these two angles.

From the older perspective, we ourselves are patterns. In fact, we are patterns within patterns. From this viewpoint, expecting us to define a pattern is unrealistic because we are part of it! For example, in the case of cancer, there is a pattern within us that transforms into another pattern, leading to our death. Another example: the water we drink is composed of patterns digestible by our body; if that pattern changes, it could become undrinkable and harmful.

Thus, we are all patterns, differing in complexity. We understand simple patterns but often ignore more complex ones because we cannot fully perceive them. For instance, the rhythm of seasonal change is perceptible to us, but larger cycles may exist that our lifetime does not allow us to comprehend. Similarly, all arrangements we encounter are patterns, part of which is comprehensible and part incomprehensible, and we mostly engage with the part we can perceive.

Question: Which aspect of patterns interests you most? Which facet of patterns is relevant to contemporary issues you explore?

Answer: For me, the contemporary event in patterns is the awareness of the pattern issue itself. In our art, patterns are significant perhaps because historically we didn’t have specialized artists. For instance, we had poets who studied astronomy, mathematicians who knew music, painters who studied medicine—essentially, they were an integration of art and knowledge. Discoveries in one field, such as mathematics, also found expression in music. Music reveals the aesthetics of sound patterns: humans realized that with a specific, yet complex rhythm, combining notes creates music—a sound pattern. This is mathematics as well, a kind of natural principle. Similar patterns appear in architecture, such as the design of mosque domes. The interplay of sky, mathematics, and music leads to discovering the dome’s pattern. Today, although we separate disciplines, historically these were integrated efforts to understand the universe, expressed through music, carpets, and other arts. We now call this pattern and continually reinterpret it.

Question: How do you see the role of patterns in contemporary design?

Answer: I would say that by understanding patterns, we are discovering rules and creating them. We advance things that exist naturally in nature but can be reproduced or even newly created through conscious effort. For instance, the Internet: by understanding binary (0 and 1) and developing it further, we created a new concept called the Internet—a world parallel to our own, in which we also exist. Our worldview helps us create new patterns, forming a new world.

Question: How does a pattern in graphic design differ from patterns in other fields?

Answer: Patterns in graphic design seem more common and visible. This is because in graphics, even very simple patterns can be seen and felt. Complex patterns also exist in graphics but may be forgotten or invisible to the naked eye. Fundamentally, however, patterns are not different across fields. Graphic design makes patterns more perceptible because it often uses them in simpler ways.

Question: How does an Iranian designer’s perspective on patterns differ from Western or Eastern designers?

Answer: Fundamentally, there is no major difference. However, pattern use by Iranian designers feels more instinctive and intuitive, like the process of composing Persian poetry. For Iranians, this is familiar because poetry is deeply embedded in our language, culture, and ways of life. In this sense, we are inherently intertwined with patterns. Comparing this with Africa, Japan, or India is difficult, but in Iran, we are surrounded by patterns from carpets to walls. Yet, this is not absolute, since we grow up in only one context and cannot experience others firsthand.

Question: What is the place of historical Iranian motifs in contemporary design? Are they Iranian, or more broadly part of Islamic cultural heritage?

Answer: This is a complex question without a simple answer. I cannot fully separate “Iranian” from “Islamic” because different historical periods in Iran have left overlapping influences. What we are today results from all of these interwoven layers. Therefore, we cannot definitively say whether a mosque in Isfahan is Iranian or Islamic. Even within Iran, churches and mosques exist side by side, each different. Many factors intertwine to produce what we see today. Islamic culture emphasizes beauty, as reflected in the saying “God is beautiful and loves beauty,” so aesthetics have developed significantly alongside Islamic culture.

I think part of the reason these patterns are not more widespread in contemporary design is due to the limited work of architects and graphic designers. To create a modern world, we must contemporize what we have rather than merely adopting Western models.

Question: How do patterns feature in your own projects?

Answer: I use simple patterns because they are attractive and evocative. However, I am more interested in hidden, invisible patterns that operate structurally. The audience may not see them directly but feels their effect. For example, viewers may stand before an image for a long time, drawn to it without knowing why—this is because a structural pattern underlies the artwork.

Even in nature, patterns are often subtle and initially imperceptible. Humans discovered them through observation, like the discovery of stars with early instruments. The hidden presence of patterns contributes to the fascination of the world, and incorporating them invisibly in art is enchanting for the viewer.

Question: Your work shows a strong connection between past and present. Is this a conscious or intuitive process?

Answer: I aim to bridge this gap. This is possible only by being aware of the past and conscious of contemporary developments. I try to imagine what would happen if modern influences were removed, at least temporarily and theoretically. Various mentors, like Hafez Mir Eftabi, inspired this approach, guiding me to the depths of miniatures and showing that what we see is not always the optimal solution. Many practices in my studio are incompatible with conventional capitalist logic, allowing for unique results. Otherwise, everything becomes repetitive and derivative.

Question: In the jurors’ panel, you mentioned that beauty is a function and cannot be reduced to just aesthetics or utility. Could you elaborate?

Answer: Anything that attracts attention can be called beautiful. Just as flowers attract insects using aesthetic principles or rams fight to continue their lineage, beauty functions as a practical mechanism for engagement. We compose poetry to convey meaning and feeling beautifully, ensuring it spreads. Proverbs survive centuries because of their form, beauty, and utility. Beauty is thus inseparable from its function, and patterns often serve both purposes.

Thank you for your time!