Talk with Jean Marc Castera

Ghazal Refalian – 2017

[This not is originally written in Persian and is translated to English by AI. Original note]

AUTHOR AND ARTIST OF GEOMETRIC ARTS

Jean-Marc Castra is a talented artist with a background in mathematics and a recognized expert in Islamic geometric art. After earning his degree in mathematics, he launched an experimental course at Paris-8 University to explore the relationship between mathematics and art and began working on geometric arabesques. At that time, there were limited resources available in this field. He worked for years, publishing his results in two books: “Arabesque – Decorative Arts in Morocco” (1999), along with numerous articles on the subject. Since 2006, he has worked on multiple architectural projects—an extraordinary opportunity to experiment and apply evolving ideas in this artistic field. His works can be seen in places such as the Grand Bazaar and the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi.

Q: Could you tell us a little about yourself? We’re eager to know how you became interested in patterns.

A: I was born in the mountains, on the border between France and Spain. My father passed away when I was 27 years old, and afterward, my mother, my two sisters, and I moved to several different places. I currently live in Paris, but my heart remains attached to the life of nomadic people. Although I always loved design, I chose to study mathematics. When I had the chance to teach at Paris University, I launched a course called Mathematics and Art, at a time when these two words were considered entirely separate.

I became acquainted with the art of Escher. I realized that his journey to Granada, Spain, was a turning point in his life. I decided to follow in his footsteps and traveled to the Alhambra in Granada. This journey became a turning point for me as well. Unlike Escher, I truly wanted to deeply understand this geometric art. I consulted books but found nothing useful, so I began my own research. It took time, and eventually, I published two books. The second book, Arabesque, is recognized as a reference for the Western approach to traditional geometry—even by Moroccan master craftsmen. I value their judgment more than that of any educated person.

I left teaching and turned to computer illustration, animation, and holography, and then began my life as an artist. Today, I do what I know best and love most.

To answer how I became interested in patterns, I must tell a story. I clearly remember being a small child with my mother in a street market; the sun was shining. Suddenly, I saw a golden round plate hanging in a shop, reflecting the sunlight—it was certainly a Moroccan metal tray with intricate geometric engravings. This image of gold, sun, and geometry fascinated me. I felt captivated… and frustrated: it was a door to a golden space, but I did not have the key.

In any case, my interest lies more in the relationships patterns create than in the objects themselves.

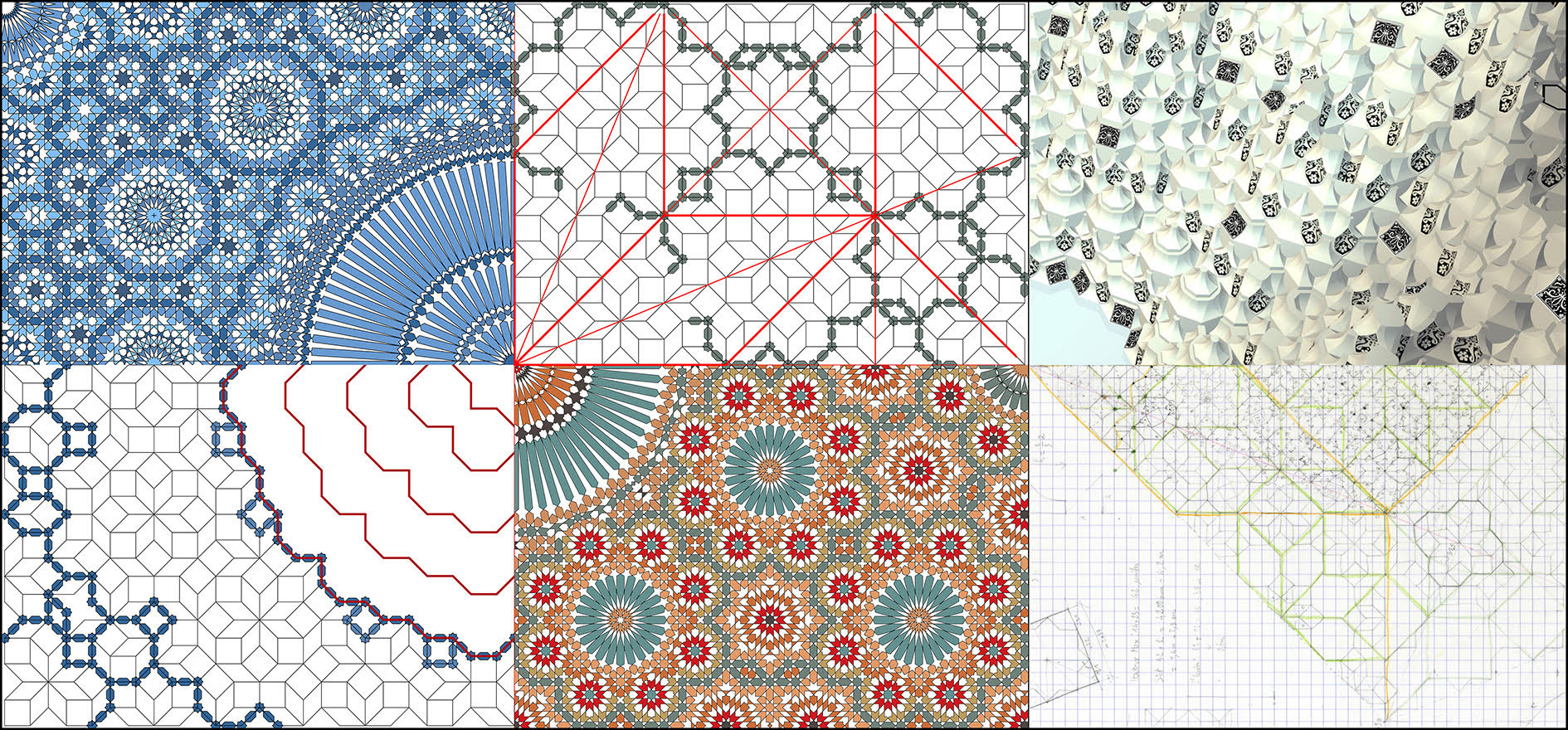

World of relations: Stars 96 and 64 and a muqarnas under a dome—all based on a single structure.

Q: How do you define a pattern? In other words, how do you categorize a design as a pattern?

A: The English concept of “pattern” is very broad. Here, we discuss patterns from an artistic or mathematical perspective.

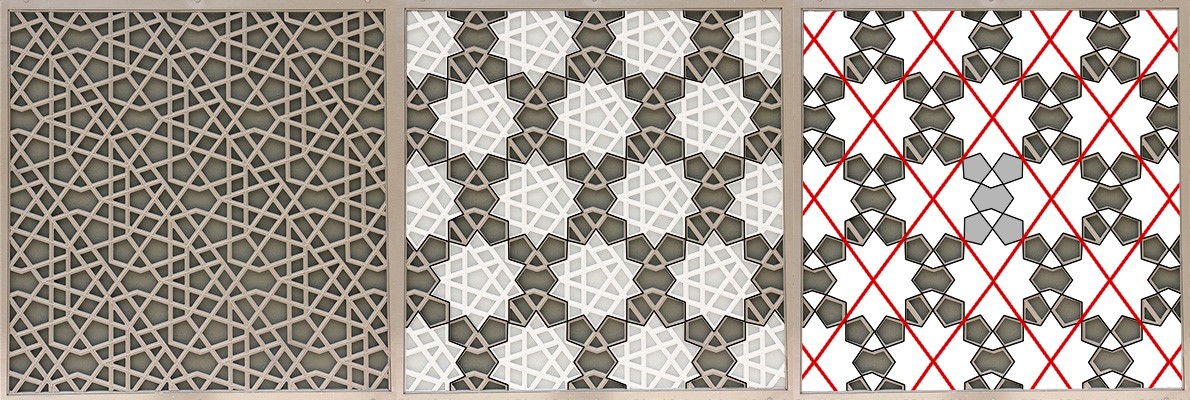

Let me put it this way: patterns are a response to the question of how to fill space (often two-dimensional) using a repeating unit. A more precise mathematical definition is: the problem of how to fill an infinite surface with a finite set of tiles so that there is no empty space or overlap. Such a pattern consists of two elements: a finite set of tiles and a structure (guidelines for using the tiles). Until the discovery of non-periodic patterns and quasi-crystals, patterns were thought to be periodic (formed by arranging a unit on a surface that can be repeated and translated, like crystals or wallpaper).

Q: Why are patterns important? What makes them attractive?

A: In other words, what gives life its significance? It’s hard to say, but simple to experience. Patterns are everywhere—even in your skin.

Q: Are patterns part of science and philosophy, and do they interact with them?

A: This is a question raised by the brilliant—yet free-spirited—French mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, who passed away in 2014. The pattern problem relates to his theory, though only a few high-level mathematicians can understand its meaning. On the other hand, mathematicians have developed a theory of patterns derived from group theory, which is useful for crystallographers and artists alike. This interaction works both ways: we can understand patterns through mathematical theory, and mathematicians can learn from patterns. Recently, this connection was highlighted by the discovery of quasi-crystals, which required extensive scientific work and led to a new definition of what a crystal is, challenging the concept of symmetry.

Q: How do you see the evolution of traditional patterns into contemporary patterns?

A: Thank you for using the word contemporary rather than modern. I consider modernity a concept outside of time.

I work on the evolution of traditional patterns. What I often see, especially in contemporary architecture, is deformation—sometimes minimal. Tradition and modernity are trendy concepts. Today, when architects need to respond to clients’ needs, do they consult a master craftsman? No—they search for patterns on the internet. Yet, the pattern they choose must be authentic and contemporary—knowledge they often lack. So, they take a traditional pattern, distort it until it is unrecognizable, and claim it is new. They are lucky because the client is also unaware.

However, even if you know nothing about patterns, you can feel if a pattern is good or bad. The danger of this approach is that people may become alienated from traditional patterns. Fortunately, some designers create excellent exceptions.

The “new pattern” in Abu Dhabi is nothing but a simple, slow pattern combined with extra lines, showing no respect for the original rules—a classic pattern lost.

Q: Do traditional patterns still hold value in contemporary times?

A: I understand the value of your question because it is expressed through a structured traditional language.

Q: What do you think about the future of patterns? In which direction are they moving, and can traditional patterns evolve?

A: In his famous—unignorable—book, Mr. Packard addresses a similar question from Moroccan master craftsmen. He said, “I am searching for an unknown flower, a flower that will come from the future.”

I believe traditional pattern art—as a living process—is necessary and can, while preserving its meaning and spirit, benefit from new mathematical concepts to continue growing. This is precisely what I aim to demonstrate in my work.

Q: How does digital media affect pattern design?

A: In the worst and best possible ways.

Q: You’ve collaborated with architecture offices. Can you tell us about that experience?

A: Foster and Partners were responsible for the Central Market project in Abu Dhabi, UAE. The client wanted traces of tradition in the facade decoration, but with a modern interpretation. The design team tried to use my book Arabesque, but it required a lot of time, and the client was not satisfied. Finally, at the last moment, they contacted me for consultation. I decided to do the design myself, which led to a passionate collaboration. My favorite project is the Masdar Institute in Abu Dhabi.

Working with architects, I realized they had lost traditional decorative knowledge. In modern and minimalist architecture, this knowledge is not taught in schools. As a result, decoration is only considered at the final stages, and patterns are applied like wallpaper. They don’t realize that geometric decoration must emerge from the structure’s growth and evolution.

Collaboration with Foster and Partners was an extraordinary opportunity to experiment with the evolutionary development of tradition. I worked with complete freedom and confidence. I learned a lot from these intelligent people, and the team dynamics were very positive. Every project produced new ideas. Unfortunately, after the economic crisis, many large projects were left incomplete, slowing the process.

Working on large projects is inspiring for a designer—it’s like a childhood dream. Once completed, it’s done. Now I want to explore new dreams, to create something good, big or small—it only needs to be good for the people, not billionaires or princes, but real people, respecting life.

Q: In contemporary architecture, there have been efforts to reinterpret geometric patterns, especially in building facades. How do you evaluate these attempts?

A: “New reading,” “modern reading”… Words, words, words. The truth is, without a deep understanding of tradition, one cannot create meaningful work—this requires immense effort.

Tradition is the result of generations of anonymous artists and craftsmen reaching high complexity—it deserves respect. If someone lacks knowledge, it is better to create something completely free from tradition than to attempt a new reading that misrepresents it. Clients may still be satisfied with imitations combined with words like “tradition” or “modernity.”

Q: Is it correct to say that contemporary professional practice requires specialized pattern designers?

A: Specialized or not, we need good designers.

And who is “we”? Obviously, many companies only want cheap designs and cheap designers. We need trained people, and this is also the responsibility of architects.

Q: As a teacher, do you believe students should start with hand design or digital tools? Is learning coding necessary for advanced pattern design? Could you explain a bit about your personal method?

A: First, dream—dream a lot. Then, the idea comes through the hand on paper. After that, any tool can be used to finalize the idea, such as computer software.

Coding can be useful but is not essential. Even without coding, one can define a generative process, like an algorithm. Working with a computer specialist can also be useful. Sometimes I get tired of doing everything alone, which is why I enjoy collaborating with skilled colleagues.

Q: Could you describe your teaching method?

A: First, students must learn to see. In Morocco, and of course in Iran, you need nothing more than careful observation. Then, design begins with a triangular grid. I teach a freehand design method for octagonal patterns, approximating square grids. Students are encouraged to find base structures and solve the pattern. Finally, they move to computers and vector design software to create patterns with precise proportions and full understanding. This is the first stage of learning. I also incorporate some games to work with tiles in a tangible way. I don’t have a single method—I have many, and I don’t believe in a universal approach.

Q: Thank you very much.